Museu de Arte de São Paulo: Picture Gallery in Transformation

Picture Gallery in Transformation Museu de Arte de São Paulo April 2016 The elevator door opens and more than 100 floating masterpieces from the 14th to the 19th century seem to be starring at the viewer as he enters. Lina Bo Bardi’s unconventional glass easels with the cement base are scattered all over the […]

Picture Gallery in Transformation

Museu de Arte de São Paulo

April 2016

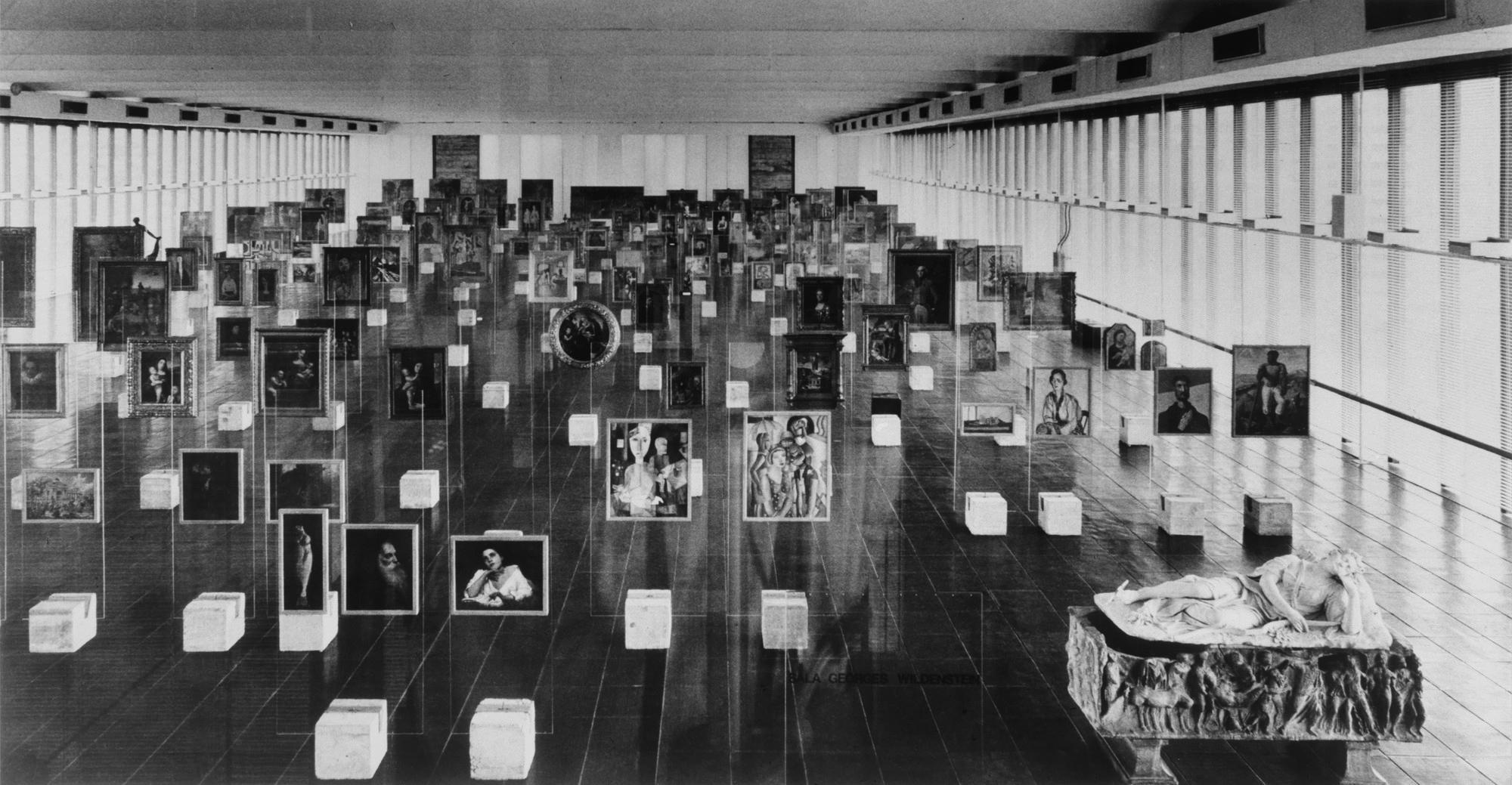

The elevator door opens and more than 100 floating masterpieces from the 14th to the 19th century seem to be starring at the viewer as he enters. Lina Bo Bardi’s unconventional glass easels with the cement base are scattered all over the open floor plan space with the large windows. They are all here: El Greco, Velázquez, Goya, Cézanne, Renoir, Manet, van Gogh, Monet, Pablo Picasso; just to give an idea. Along with them a few Brazilian artists, from the same time-frame but also a few more contemporary ones.

It is not often that one can see all these European Masters in Brazil but the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP) has the largest collection of European art in Latin America and the Southern Hemisphere (sic). In ‘Picture Gallery in Transformation’ one can see 119 works out of the 8,000 the collection holds. But this is not MASP’s only preeminence. Its impressive building, designed in 1968 also by Bo Bardi, is considered to be iconic in Latin American architecture. It is a modernist play between void and volume; a solid structure in perfect dialogue with the open air ground floor, a cool haven for the sun burnt city dwellers. The same elements of volume and lightness that Bo Bardi used when creating the glass easels 50 years ago. Adriano Pedrosa, the internationally acclaimed curator who was appointed Director in 2014 with the mission to ‘restructure’ MASP, took them out of storage for this exhibition. Testing these avant-grade display structures in the contemporary context of the present, they only prove how relevant they still are; even though they did create controversy in the art circles back in the 70s.

The fact that the visitor can walk around the space, amongst a forest of 17th century masterpieces is very liberating and definitely very different to what we have been used to when visiting similar exhibitions, were the works are hung in a sterilised manner on the white walls. Here, there is a level of familiarity and physical engagement that makes it all much more interesting, personal and humane. The paintings become sculptures in the space, which one can view from all angles and from up close. This painting-as-sculpture approach reveals one more key element: the work’s back side. Doesn’t sound exciting, but it really is. Not for the label information that lies on its surface (which is always helpful) but for all the small elements that usually go unnoticed; the nails, the wooden details, the canvas, the stretcher, in the imaginary a thread connecting the past to the present; all part of the experience. Each painting becomes a recto-verso artwork; both sides matter, front side art, back side text; front side the image, back side its semiotic equivalent. When reaching the end of the exhibition, upon turning around and facing the room, the view is unique and unusual; 119 back sides of Old Masters works. When walking around the exhibition from the end towards the beginning, a new conceptual narrative is revealed; the signifier becomes the signified.

There has been a lot of discourse regarding the way labels should accompany works of art; should they be in large fonts or in small, should they exist or not at all, what should their content be, all relating to the given impact a label has to the viewer. It is often that people first reach out for the name of the artist (is it a well known artist, or not?), or for the title of the work, hoping to create their impression of the work based on that information. On the other hand, this reflex is no surprise, as in contemporary art this information is often an important tool for interpretation. Given that most visitors spend more time reading the labels than actually seeing the work (a total of ten seconds spent in front of an artwork and seven of them to read the label), it is quite liberating that here the viewer is free to enjoy the paintings without being imposed by the work-related information which mediates and interferes with his sense of liking based on the importance of the artists. Plus, for the more playful ones, they can always test how good their knowledge on European masters is by guessing the right answer.

All these exhibition related decisions were part of Bo Bardi’s exhibition designs making this exhibition a true revival of the initial one of the ‘70s: the easels, the forest-like layout, the labels. The only thing that has changed is that back then the works were presented in clusters based on the artistic movements each one belonged to, as now they are presented in a chronological order. This change facilitates the notion of moving forward, the dynamic of the past towards the future; a concept very important to Director Pedrosa. This change in presentation, also allows the viewer to witness the evolvement of the art through the centuries and the different ways the artists expressed themselves through the same medium, that of painting. But again it is just a way of organising the massive number of works; the viewer is invited to experience the exhibition their own way and bring together different works and create unexpected juxtapositions and dialogues. Truth is, viewing so many works in just one space is quite unique; it would need endless rooms in any other museum.

Speaking of medium, apart from painting, the exhibition includes a few sculptures as well: nine in total, among which works by Rodin and Degas (amazing Little Dancer, aged fourteen, 1880) as well as a work by Brazilian Abelardo da Hora. Wandering around 17 rows of glass easels which inevitably create an invisible labyrinth, these sculptures act as landmarks to the narrative; small breathes to the route. The totality of the exhibition covers a time frame of almost seven centuries (14th-21st), so when viewing the totally unexpected 400 BC sculpture of goddess Hygeia and the pair of Chinese Warriors from the Tang Period (618-907), it is quite a surprise. These sculptures didn’t just happen to be there, their presence facilitates a cause- so that’s at least a bit odd. The totally irrelevant to the rest of the show bold choices, in style and time frame, do make you think. What is this exhibition really about? Why didn’t the curators decide to keep a stronger curatorial angle to the collection’s vast content? What’s the need of presenting a bold amount of treasures of the past without a specific context, today?

Masterpiece-exhibitions bring in mind post-revolutionary France (let’s not forget Arthur Danto’s definition of masterpieces that they are ‘the works you would steal if you were Napoleon’), where exhibitions were synonymous to royalty, aristocracy and a narrative of turning Paris into ‘the capital of free New Europe’. Since then there has been a very close relationship between masterpieces and museums; the more important the collection the more important the museum, the more the institutional status. And the lack of the ability to afford such a collection, is one of the reasons why the Museum had to reinvent itself to the New Museum which had a more conceptual edge and content.

Then maybe, MASP is reintroducing itself to the public by showing off its thick collection of treasures vindicating its position in the museum network, next to MoMa, the Tate Modern and the Center Pompidou. But MASP is not just another Museum with an important collection; it’s a museum of the periphery. History has been written in a Eurocentric way and the postcolonial discourse vividly describes the ways that non-european and non-western cultures have been exoticized in the past and that explains the importance of a Western Collection in a Museum. The majority of the most important masterpieces belong to the largest museums of the West, so the fact that this collection is owned by a Museum in the periphery, that of Sao Paulo, Brazil, has its own great significance in the museum network dynamics. On a regional level, it is very important that such a collection exists and provides the audience with the opportunity to experience these works from up close. Then again, for the international art world, in the times of the new/critical museum, MASP didn’t really need an exhibition of Old Masters to establish itself; not anymore at least and Pedrosa knows that. Not only that, but he has also been very explicit about how the title ‘Transformation of the Picture Gallery’ refers apart from the exhibition, to the Museum as an organization as well.

So, just at the moment that you were about to sigh at the thought of another same old exhibition, you take another look around in the space and Bo Bardi gets in the picture. Showing an Old masters exhibition by taking out of the arsenal Bo Bardi’s avant grade glass easels and using her exhibition design, fifty years later, in a different context from the one in the ‘70s, well that’s an interesting idea. Because, the exhibition might be the same on paper, but the world (and the art world) was a different place in the ‘70s, when the ‘Western’ narrative was still strong. Today, to say that MASP is ‘reshowing’ Bo Bardi’s exhibition could be just a mere pretext; a pretext to make a different point.

MASP is taking the western model of art with all of its semiotic discourse and is flipping it around with the use of an innovative display method, the glass easels. Think about it as if Cinderella was going to the party at the Palace, all dressed up, wearing her nice gown and jewellery but underneath was wearing her designer sneakers, subverting all protocols. Bringing avant-garde Bo Bardi on board who has been a reference point in Latin American Architecture, who has brought controversy in museology by liberating the mausoleum-museum type with her ideas; well, that’s a good way to get the international attention and get the discussion going. MASP is presenting a traditionally ‘western’ exhibition in the most unconventional and non-traditional way; on glass easels, away from the walls, with their labels at the back, a forest of Old Masters facing the entrance, giving a floating effect to the exhibition experience. MASP in other words, is already one step ahead, by just utilising its collection and its 50-year-old archive. And all that, from the periphery of Brazil. How about that? Museu de Arte de São Paulo turning into the essence of the new, the critical Museum, acting from the periphery, challenging and questioning the supremacy of the west.

Still, the balance between the ‘centre’ and the ‘periphery’ has changed through the years. Globalisation and postmodernism fragmented the notion of the centre, they broke the ‘Western’ narrative and gave priority to pluralism. In other words, they opened the door to the periphery to be heard and to be present. And that’s what MASP is interested in doing. It is making its cultural policy by showcasing its own treasures; scattered Brazilian artists amongst European. Some of them are chronologically synchronised with other participating works; a dialogue between Europe and Brazil in terms of artistic production. As we get closer to the end of the show, MASP makes its proposal for the future, a future with a Brazilian stamp on it. The last three works (the most recent to the present based on the layout), are the only representative of the 20th and 21st century, all by Brazilian artists and each one of them with its own semiotic value.

Rubens Gerchman’s Air superlative Primer (1967-1972) is a text based sculpture and even though it bears no aesthetic coherence to the rest of the exhibition, the work is symbolic of the presence of Brazilian artists in the international dialogue. The Bride’s Wake (1974) by Maria Auxiliadora da Silva, a naive painting aims with its presence to acknowledge this out-of-the-canon-genre of art that Pedrosa wants to incorporate in a museum context. Let’s just hope that Pedrosa’s intention to focus on Brazilian out-of-the-canon art won’t make him fall into the trap of creating the exotic cliche of the ‘other’, the ‘Latin American’ as stereotyped in the past.

Marcelo Cidade, ’Suspended time of a provisional status’ (2011-2015)

And then, after 119 works, we reach the very last work of the show. Number 119. ‘Suspended time of a provisional status’ (2011-2015), a bulletproof replica of Bo Bardi’s glass easels which appears cracked by two bullets by Marcelo Cidade. Bo Bardi’s easels were created almost 50 years ago, only 35 years later they were destructed by the museum authorities and in 2015 were brought back as a vehicle to lead the future of the museum. Too many provisional statuses by different authorities. Notions of creation and destruction, innovation and conservatism; past and the future, cultural and sociopolitical power are being challenged. Cidade’s work, positioned here as the very last work of the exhibition ‘Transformation of the Picture Gallery’, in this new era for MASP, has its own significance and semiology on a different level as well. Through the gesture of violently destroying Bo Bardi’s easels through Cidade’s work, MASP leaves behind what it feels it holds it back in the glories of the past, in order to liberate itself to conquer a future free of its own history. ’In order for one to see the future of the Museum, one first needs to look back’ Adriano Pedrosa says. And by shooting it down, MASP can reinvent himself and move on to more exciting paths.

With these thoughts the exhibition has come to its end. This very last work is located just across the entrance, at the other side of the room. You turn around, you see the endless paintings, the back sides of the works- each one of them representing some of the finest works in the history of art, the easels, these iconic symbols of the avant grade of yesterday, then the bullet marked work by Cidade; it really is all part of an ever-ending transformation.

—-