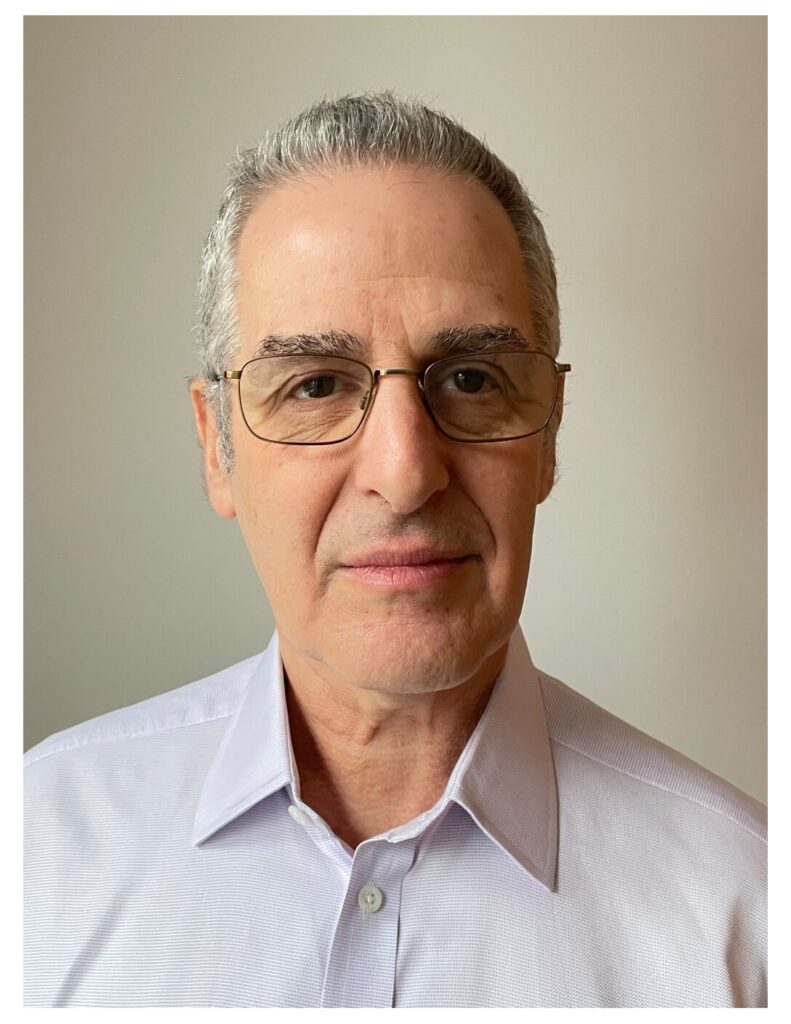

Mark Mazower: A lot of harm is done in the world through lack of imagination

The great historian, author and Columbia University professor talks to Parallaxi about the need for historical study, and Thessaloniki, the city he has explored thoroughly

Mark Mazower is the man who researched and recorded the history of Thessaloniki through a book that can well be described as the textbook of the city’s modern political history (Thessaloniki, the city of ghosts).

Last (Friday, 24/1) the city council of Thessaloniki awarded him the distinction of Honorary Citizen, at a special event held at the City Hall.

The British historian, writer and professor of Columbia University teacher talks to Parallaxi about what he has learned from his involvement with Thessaloniki, its advantages, its Sephardic identity and the importance of historical research and study. The interview was conducted a few hours before he “flew” from New York, with his busy schedule not helping the longer conversation.

What did you learn from so many years of dealing with the history of Thessaloniki? What elements did the city lose and what elements did it gain over the centuries?

«I learned about history and how we tell it. We are used to telling ourselves the stories of ‘our’ city. But what are the stories that the city tells itself? In other words, I learned to think about the perspective from which historians recount the past and how it shifts depending on where they stand and how difficult it is to justice to the true history of a city as rich in the past as Thessaloniki».

How much ‘damage’ has the silencing of history done to Thessaloniki the past decades?

«Actually, my experience of the past few decades is not of silencing. In fact, the city has been pretty obsessed with history since 1912 at least. Ever since it became part of Greece history was regarded as a very important element in its identity and historians began to work systematically on the history of the city. With the expansion of the university system after the second world war, this study became professionalised. With Greece’s growing intellectual connections with Europe and the US, history became internationalised and more and more people became interested in Thessaloniki’s history. The end of the Cold War, the wars in Yugoslavia and the Politistiki Protevousa all led to a kind of history boom. Today I think the city is fortunate that many people, many young people, are passionate to research and recover all kinds of aspcets of its past».

What was the contribution of Sephardic Jews in shaping the identity of the city? Do you feel that this is not sufficiently recognized today?

I think more attention has been paid in recent years to the Sefardic contribution to the city, at least so far as the 19th and early 20th centuries are concerned. Probably more could be done and especially for the earlier centuries. There are two obstacles. One is languages: to make a real contribution you would need to know four or five languages and few people manage to do this, and fewer still are capable of writing interesting history by the time they have mastered them. The other obstacle is the way historians carve the past up into fields: thus Ottomanists write about Ottoman Thessaloniki from the Ottoman sources; Jewish historians use rabbinical responsa; and historians of the Greek city use consular files and what few sources in Greek survive. It takes a surprising effort to get them to talk to one another.

Thessaloniki lived for many years in the shadow of another great city, Constantinople or Athens. Can it ever become the first, and should that be its goal?

«Is this a competition? The joy of Thessaloniki is that it was never burdened with the responsibility of a state capital and yet it flourished through trade, migration and cultural exchange. Its asset is its geography – its sense of being at a crossroads – and this remains a strength over time».

What does the study of history ultimately teach us? Not to fear or do you often feel that it is instrumentalized to foster hatred?

History can be mobilised for all kinds of purposes. I think a lot of harm is done in the world through lack of imagination. Political leaders indifferent to the consequences of their actions, incapable of putting themselves in the shoes of those affected, are responsible for a good deal of suffering, HIstory does not teach lessons but it can teach imaginative sympathy and help one see how very different things have been in the past, how differently they can seem to different people and hence how hard it is to see oneself in the eyes of others. Plus: it is enjoyable to lose oneself in the dramas of the past.

Moments from the award ceremony

*Mark Mazower is a historian and writer, specialising in modern Greece, 20th century Europe and international history. He read classics and philosophy at Oxford, studied international affairs at Johns Hopkins University’s Bologna Center, and has a doctorate in modern history from Oxford (1988).

His books include Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44 (Yale UP, 1993); Dark Continent: Europe’s 20th Century (Knopf, 1998); The Balkans (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2000); and After the War was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943-1960 (Princeton UP, 2000). His Salonica City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950 (HarperCollins, 2004) was awarded the Duff Cooper Prize. In 2008 he published Hitler’s Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe (Allen Lane) which won that year’s LA Times Book Prize for History. His most recent book is What You Did Not Tell: A Russian Past and the Journey Home (Other Press, 2017).

He is the founding director of II&I: the Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination at Reid Hall in Paris and his articles and reviews on history and current affairs appear regularly in the Financial Times, the Guardian, London Review of Books, and the New York Review of Books.